Painting corners: How do you make decisions when your choices have unknown pros/cons?

(My secret sauce for decision-making. So simple… I must be stupid to benefit from this.)

The background:

For the past three summers, I’ve spent a week in the outdoors with my friends Ryan and Matt (one of those rare types with zero Google presence). We’ve gone backpacking, canoing, overseas, etc. These trips were great fun, rebooted my perspective with a week completely offline, and helped me build some incredible friendships.

That is, until last summer. Matt was starting school at the end of August, and Ryan was working until early August. And it just so happened that I’d been offered the chance to spend August at TechStars.

Decision: TechStars or my friends?

I spent two weeks agonizing over the decision, knowing that I was picking between two attractive options. The worst part was I didn’t know exactly what would be the outcome of my TechStars experience, nor whether the three of us could get together over Thanksgiving (the only potential compromise.)

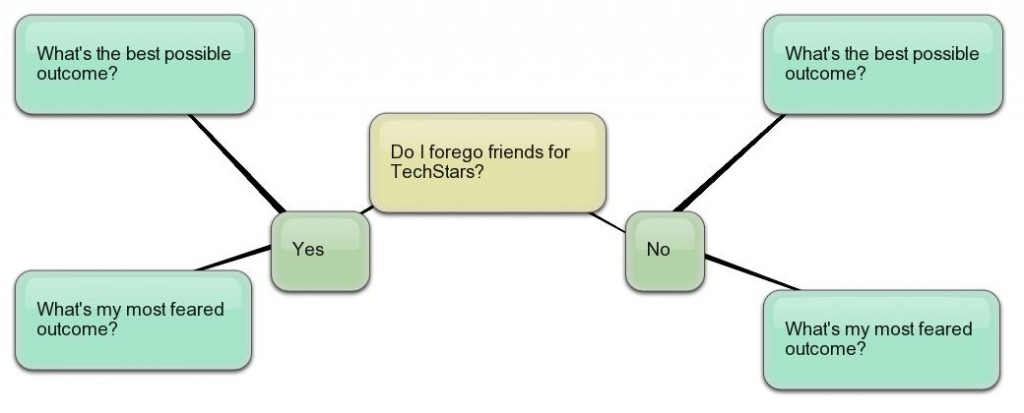

How do you make decisions when your choices have unknown consequences–when you don’t know the pros/cons?

You paint the corners. ‘Cause you almost always know the absolute best and absolute worst. You just don’t know the probabilities.

This oversimplifies complicated decisions into a binary outcome.

Eg, if I go to TechStars, the best outcome included massive learning, extending my network, and connecting with Matt and Ryan over Thanksgiving. The worst outcome was a month in Boulder minus the opportunity cost of staying home.

If I go with friends, the best outcome was making money for a few weeks, plus spend a week with friends. The worst that happens is I make a little money, spend a week with friends, and forgo opportunities from TechStars.

The pros/cons are unknown–or rather, known outcomes with unknown probability..

I chose TechStars, and was also able to connect with my friends over Thanksgiving.

(Note: I first read about “Best-worst case analysis” in Ben Carson’s book, Take The Risk–thanks Jerome! I’ve found these four questions make most of my decisions very easy.)

Steve Blank provides another decision-making heuristic:

Think of decisions of having two states: those that are reversible and those that are irreversible. An example of a reversible decision could be adding a product feature, a new algorithm in the code, targeting a specific set of customers, etc. If the decision was a bad call you can unwind it in a reasonable period of time. An irreversible decision is firing an employee, launching your product, a five-year lease for an expensive new building, etc. These are usually difficult or impossible to reverse.

My advice was to start a policy of making reversible decisions before anyone left his office or before a meeting ended. In a startup it doesnt matter if youre 100% right 100% of the time. What matters is having forward momentum and a tight fact-based feedback loop (i.e. Customer Development) to help you quickly recognize and reverse any incorrect decisions. Thats why startups are agile. By the time a big company gets the committee to organize the subcommittee to pick a meeting date, your startup could have made 20 decisions, reversed five of them and implemented the fifteen that worked.